“Vacation cutting.” I hate that term.

Placing the words next to one another is a contradiction. When I think of a “vacation,” my mind wanders into the direction of glistening gold beaches and marine blue waters with soft rolling ocean waves. I think of happiness and the comfort of a warm blanket.

The term “cutting,” however, does not make me feel pleasant. The negative connotation of the word brings up images of skin and scissors. Or maybe it was a knife. I’m not quite sure.

Put together, the term is used to describe the process of a young girl being taken out of her country of residence to have female genital cutting (FGC) or, as it is more commonly known, female genital mutilation (FGM) performed.

“Vacation cutting” happened to me.

I’ve told my story before, and you can read more about it here.

I was born in the United States, and at the age of seven, on a regular summer vacation to India to visit relatives, I was taken to a dilapidated building in South Mumbai to have a procedure performed. My mother and aunt handed me over to some older women, who put me on the ground, raised my dress, and cut a tiny piece of skin off my clitoral hood. My mother held me tight afterwards, comforting me, and I was given a soda to help me feel better.

It had happened to her. It had happened to her own mother, my grandmother. It was a practice that was considered necessary to grow up to be a good Dawoodi Bohra Muslim, Indian girl.

I hate the term “vacation cutting” because it feels like a misnomer that cannot accurately explain how a practice like FGC can continue.

What happened to me was not a vacation. But it was also not done out of malice. It was done because it was considered a social norm, a rite of passage, a common procedure that every young girl had to undergo, in a manner that was similar to the idea that every girl got her period.

It wasn’t until I reached college that I understood FGC to be a form of gender violence, a human rights violation, and a procedure that had been criminalized in the United States in 1996 — six years after I had had the procedure done to me. In college, I began to wonder why I had had to undergo it.

This question of “Why?” led me to delve further into the intricacies of how such a practice could continue.I researched it online, I spoke to others who it had happened to, I spoke to academics, and I connected with NGOs working on the issue. I learned much. I also learned little about what exactly had happened to me.

I learned that the World Health Organization had divided FGC into four categories, and that what happened to me fell under the Type 1 Category.

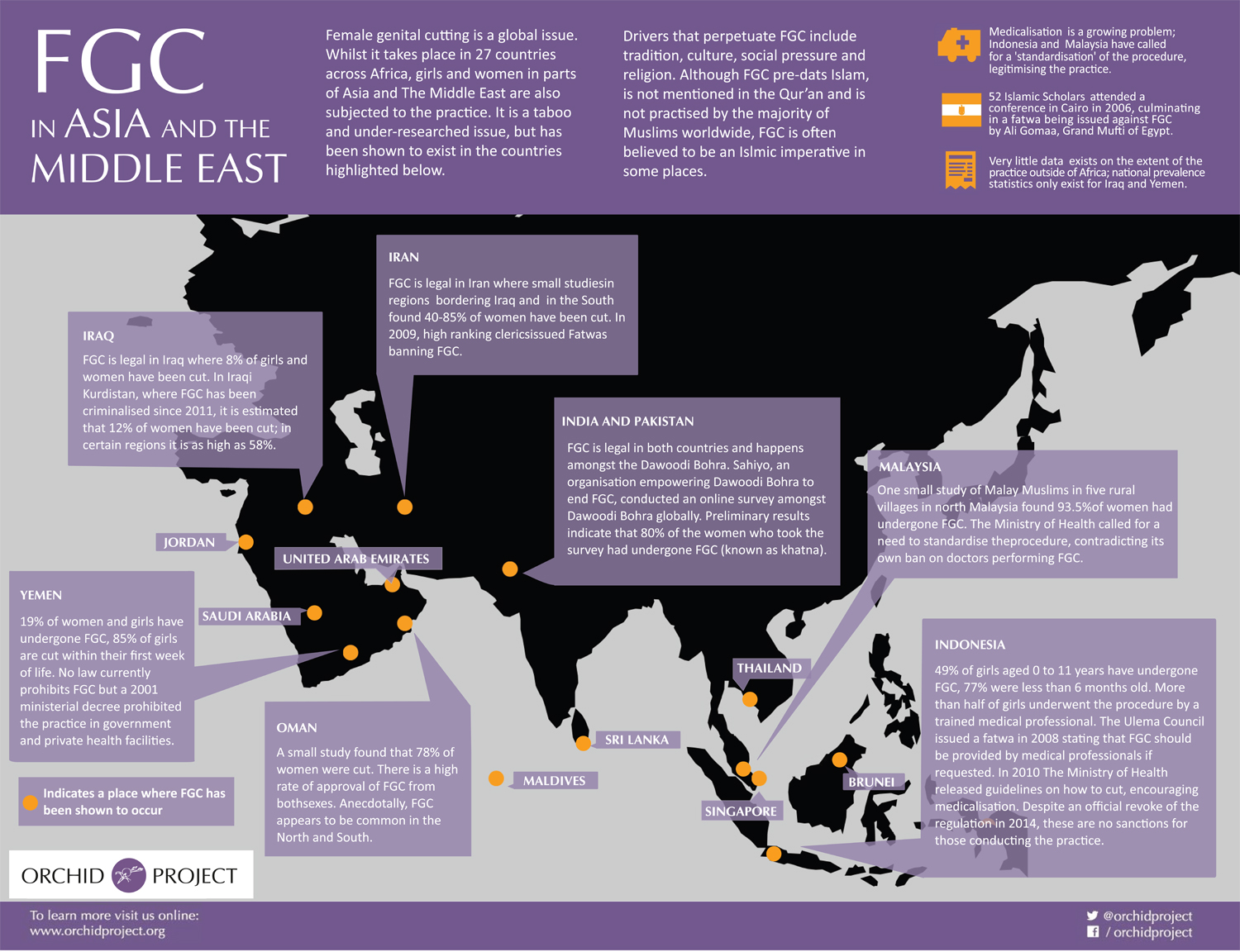

I also learned that, at that time, FGC was considered to be a mostly African practice. The research that had been done on it referred to countries such as Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Ghana, to name a few.

There was little to no mention about FGC happening in India, let alone that US-born women such as myself had undergone the procedure. My story had been left out of the research. Millions of other little girls — who had ethnic and religious ties to countries outside of Africa — had been left out too.

I needed to show that FGC was more widespread than previously acknowledged.

In 2008, this lack of knowledge led me to pursue a Master of Social Work thesis called, “Understanding the Continuation of FGC in the United States.”

From my research, I learned that FGC had continued in the United States because of its ties to the idea of maintaining a cultural identity. More surprisingly, I learned that clitoridectomy (a form of FGC) had been a regular medical treatment in the US and Europe up until the 1940s, and used to treat “conditions” hysteria, nymphomania, and masturbation in women.

Most importantly, I learned that the continuation of FGC was not tied to a specific religion or an area of the world, but was erroneously tied to Islam even though the origins of the practice predate both Islam and Christianity. Its continuation was also erroneously tied to Africa, though reports of FGC occurring in South America, Russia, and other parts of the world were also circulating.

In the last few years, the United States, India, and international bodies such as the UN have begun to acknowledge that FGC is more widespread than previously believed.

In 2013, the United States passed a law banning “vacation cutting” — it was a loophole that previous US federal legislation had not addressed.

In India, the country where I underwent FGC, survivors have begun speaking out in mass about their experiences, and activists are encouraging the government to pass legislation to ban it.

The UN has acknowledged the pervasiveness of this practice by including in their Sustainable Development Goals the elimination of FGM in all countries, instead of just in FGC-high prevalence countries, as previously tracked.

Today, it is believed that half a million women and girls have undergone FGC in the United States.

There are still no statistics for India, but Sahiyo, an NGO I co-founded, learned that amongst the Dawoodi Bohra Indian population — both those in India and diaspora groups around the world — 80% of women had been cut. Globally, it is believed that 200 million women and girls have undergone FGC.

[Tweet “”Half a million women and girls have undergone female genital mutilation in the US.””]

As global migration continues, unfortunately, the spread of FGC across the globe will continue, and the need for health workers, social workers, lawyers, legislators, anti-gender violence advocates, and child protection workers to be educated on FGC will be vital if they are to help survivors.

This is particularly important in the West in a time when the practice of labiaplasty — which falls under Type IV FGM — has become one of the fastest-growing cosmetic surgery procedures for women in the US, UK, and Canada, and botched surgeries are often reported.

Yet, hope exists.

Sahiyo found through its work and through our online global survey that many people within the Dawoodi Bohra Indian community are not okay with the practice continuing. Tostan, an NGO based in Senegal, found that many villagers have successfully abandoned the tradition.

More and more stories of activists from the around the globe speaking up against the practice are being heard. Social media is playing a vital role in spreading the message that FGC should not continue.

Most importantly, people both from the FGC practicing communities and non-practicing communities are talking about it — publicly.

The biggest hurdle to enacting social change is not having the ability to talk about that which needs change.

Often, it is human nature to remain quiet, to not cause a stir, to not antagonize. For centuries, talking about FGC publicly was considered taboo in many practicing communities. Today, we see that silence being broken. We see voices rising to a crescendo. They are demanding an end.

Change has begun and can only continue, if you too openly discuss Female Genital Cutting and the need to abandon the practice.

So let’s talk about it.